There was a time when leaving or staying in Cuba was considered a political decision. Going to Miami, or ending up there, instead of some other city in another country, was something that in many minds acquired importance.

There was a time when leaving or staying in Cuba was considered a political decision. Going to Miami, or ending up there, instead of some other city in another country, was something that in many minds acquired importance.

But it was practically impossible for a Cuban artist to continue his career in Miami without paying political tribute to the anti-Fidel current dominant in the city – actually anti-Cuban.

Then came the times of the cultural exchange and later diplomatic relations with the Obama administration, and there was a moment of hospitality in Miami for artists who lived on the island. Competition between media programs and channels, more concerned about the ratings that featuring these artists could garner, kept hosts and programmers on good behavior for a while, welcoming on their sets every musician, comedian or actor living in Cuba who visited Miami.

The television industry that had multiplied its profits with a counter-revolutionary editorial line found itself limited, at that specific moment, to harassing artists arriving from the island at airports and asking hostile questions. Their customary commercial product, hatred toward everything Cuban, was no longer as lucrative.

The relief felt, after the traumatizing effect on families of George W. Bush’s aggressive policy, with restrictions on travel and remittances, was noticeable in an environment in which thousands of Cubans living in Florida were investing in the new possibilities opened up by self-employment in Cuba. At that time, for the anti-Cuban right in the Miami media, things were going in a different direction.

As the second decade of the 2000′s progresses, the rise of social media means that television formats, which had benefited from the use of Youtube, are beginning to lose ground to the growing volume of content produced directly for this platform. The circulation of excerpts of talk shows is beginning to be surpassed by the production of programs broadcast via streaming and viewed by a growing number of subscribers to digital channels.

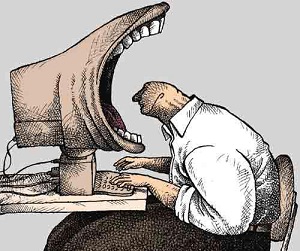

Today, in 2020, the political media industry in Miami is much better positioned on the Internet, moving away from the traditional press and TV – without abandoning them completely – building its presence on Youtube, with new faces, along with a series of aggressive web pages. Unlike television, these programs made for streaming and online viewing, assume even greater impact with the option of commenting and sharing, which social networks offer their audiences.

For artists residing in Cuba, the anti-Cuban media’s positioning means increasing attempts to poison relations between the Cuban community in the United States and their country, as well as efforts to end performances in the city of Miami, along with any economic benefits, which had become possible during the era of cultural exchange.

While the political ambiguity of a group of artists generates largely indifference in Cuba, that right-wing in Miami, with its resurgent hatred, is not willing to forgive anyone: You join the anti-Cuban discourse or you don’t come to Miami. But the new media and social networks go farther, seeking to extend their persecution to those who, in Cuba, defend their right to a political opinion of their own. With the threat of media lynchings, they attempt to silence and intimidate artists who might speak out against the blockade or in defense of any value the Revolution has bequeathed to them.

In an interview with Russia Today, singer-songwriter Amaury Pérez commented, referring to political expressions by artists on social media: “There are people who should be defending some things I have defended. They are scared to death. Because you need to have a tough hide to put up with the things that are said about you.”

Every day, we are witness to how the digital machine dedicated to the media war against Cuba positions any statement by an artist that is politically useful to them – as if it were an event of great public interest – casting them as “opinion leaders” by multiplying their personal comments on Facebook,

In many cases, the low number of likes and comments an artist may receive, when posting their work on their own, is dramatically increased with a publication of this nature.

For several of these artists, the instantaneous, but ephemeral “celebrity” this positioning gives them, which must be constantly reactivated, becomes a kind of publicity. On the one hand, it feeds their ego, and on the other, gives them artificial recognition that few have achieved as a result of their work, while allowing them to keep their promotional profile active.

This mechanism has even attracted individuals well positioned in commercial music, who seemingly would not need to attack the country where they learned their art and has recognized them. When they join the media chorus against Cuba, more than anything else, what they generate is shame.

There are also more than a few individuals who seek acceptance and attempt to maintain sympathetic ties with the Miami art market, which is not willing to include artists who presume to develop a career naively removed from politics.

As a consequence of a poem singer-songwriter Ray Fernández posted on Facebook, in which he condemned acts of vandalism against busts of Martí committed earlier this year – which others seemed afraid to denounce – he was obliged to face a pack of wolves on the web, attacking him with insults of all kinds. Today, in this difficult year for Cuba and the world, it is worth remembering the words with which the cultured musician responded: “Let no one doubt that these are defining times.”

(Source: Granma)