Given the increase in U.S. imperial aggression and arrogance, many Cubans are being heard these days paraphrasing General Antonio Maceo, on the occasion of his historic statement in Mangos de Baraguá, in 1878, when responding to a surrender agreement known as the Zanjón Pact, he said, “No, we do not understand each other.” I agree with them, we cannot understand the U.S. government, for many reasons, among them because we make an effort to give words the interpretation they deserve.

Given the increase in U.S. imperial aggression and arrogance, many Cubans are being heard these days paraphrasing General Antonio Maceo, on the occasion of his historic statement in Mangos de Baraguá, in 1878, when responding to a surrender agreement known as the Zanjón Pact, he said, “No, we do not understand each other.” I agree with them, we cannot understand the U.S. government, for many reasons, among them because we make an effort to give words the interpretation they deserve.

In the Helms-Burton Act, the terms “confiscated property” and “confiscated assets” are used regularly. As Dr. Olga Miranda Bravo explains, these terms are in no way “similar to nationalization,” defined as an act by which a nation, in a legal process, can, for different reasons, order the appropriation of private properties and place them within the public treasury.”

The confiscation of assets is an accessory legal act, subsequent to the commission of a crime, which implies, in addition to a penalty, the restitution of property ill-gained, with no right to compensation.The Council of Ministers, in use of powers recognized by the Fundamental Law of the Republic, February 7, 1959 – broadly and specifically inspired by the 1940 Constitution – enacted Law No.15 on March 17, 1959, which ordered the confiscation, and consequent adjudication to the Cuban state, of assets owned by Fulgencio Batista and all those who collaborated with his dictatorship, recognized as responsible for multiple crimes, as set forth in the Code of Social Defense, in effect at that time.When the Helms-Burton Act refers in its section 302 of Title III to trafficking with property confiscated by the Cuban government, it is protecting the very criminals cited in Law 15/1959, whose assets were confiscated because they had committed crimes.

Nationalizations, as state acts, are based on a country’s sovereignty, and therefore every state is obliged to respect the independent right of all others to conduct such processes, which constitute acts of economic justice to benefit the entire people and, yes, do imply adequate compensation.

The first nationalizations took place in Cuba when the Agrarian Reform’s first law was enacted, and established compensation with 20-year government issued bonds which accrued 4.5% annual interest.

With regard to the Agrarian Reform, on June 29, 1959, the U.S. government delivered a diplomatic note to the Cuban government, stating that, in accordance with international law, the United States recognized that a state has the power to expropriate within its jurisdiction for public purposes, in the absence of contractual provisions or any other agreement to the contrary, however, this right must be accompanied by the corresponding obligation on the part of a state that this expropriation will entail the payment of “prompt, adequate, and effective compensation.”

The arrogant, interventionist note attempted to unilaterally establish the form in which compensation would be provided, as opposed to an indemnity agreed upon by the parties involved. Any such demand is invalid, given that the only right internationally recognized is “appropriate” payment, in accordance with laws in effect within the country of the government conducting a nationalization. Faced with his affront to the nation’s dignity and sovereignty, the Cuban government responded that such interference in the country’s internal affairs would not be accepted.

Always willing to discuss any such disagreement with the United States, on February 22, 1960, via a note from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the U.S. government, Cuba proposed reopening negotiations via diplomatic channels, on the basis of equality, as long as the “U.S. Congress did not adopt any measures of a unilateral nature to prejudice the outcome of the aforementioned negotiations, or that could cause damage to the economy of the Cuban people.”

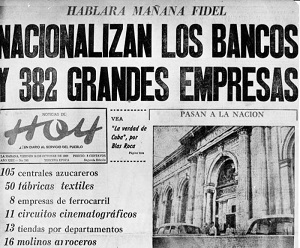

The arrogant response was not long in coming: “The Government of the United States cannot accept the negotiating conditions expressed in his Excellency’s note, to the effect that no unilateral measures will be taken by the government of the United States that could affect the Cuban economy or that of its people, by either the legislative or executive branches.”Consistent with this imperial position, dismissive of any civilized dialogue, the Eisenhower administration established the principles that have guided U.S. administrations for all these years, evident in the infamous memorandum of April 6, 1960, less than a month after the previously mentioned exchange of notes, presented by Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Lester Mallory, in which he referred to our Revolutionary government, saying: “The only foreseeable means of alienating internal support is through disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship… Every possible means should be undertaken promptly to weaken the economic life of Cuba… denying money and supplies to Cuba… to bring about hunger, desperation and overthrow of government.”Other nationalization laws to benefit the people would be promulgated by the Revolutionary Government: 890, 891, 1076, the Urban Reform Law, etc.Noteworthy is Law 851 of July 6, 1960, whereby nationalizations were ordered, for reasons of public utility and social interest, of the assets of U.S. citizens and legal entities, with the corresponding compensation established. The payment of expropriated property would be made, after appraisal, in government-issued bonds.To guarantee the repayment of these bonds, a fund was established by the Cuba state which would be awarded 25% annually of the foreign exchange earned from sugar purchases by the United States in excess of three million long tons, for domestic consumption, at a price no less than 5.75 cents of the British pound. Toward this end, the National Bank of Cuba opened a special account in dollars designated: “Fund for the Payment of Expropriated Assets and National Enterprises of the United States of America.”

The bonds would accrue interest of 2% annually and be repaid within a period of no less than 30 years.

The U.S. government, fully aware of the damage to be caused its citizens who would be denied access to compensation granted by Cuban law, canceled the sugar quota that historically had been agreed upon with Cuba. Given the role of sugar in the nation’s economy, the essential basis for payment of adequate compensation was undermined, to which the economic, commercial, and financial blockade was added.On the other hand, the will of the Cuban state to dialogue, and come to agreement on compensation for nationalizations, made possible the reaching of accords with Switzerland and France (1967); Great Britain, Italy, and Mexico (1978); Canada (1980) and Spain (1986).In these compensation plans, it was expressly agreed: – Plaintiffs are represented by their government in government to government negotiations, and must be citizens of the claimant state at the time the property in question was expropriated. – The global agreed-upon figure of compensation is not that cited in the claim, but the result of fair assessment. – The establishment of terms and payment methods is in cash and in kind.Thus, let us ask, on what legal basis does the United States assert its courts’ right to hear and rule on sovereign acts of another state and against citizens of third countries? Only imperial arrogance, flagrant disregard for international law, and disrespect for other countries of the world, can explain this procedure.

(Granma)