Needed today are new readings of Fidel’s “Words,” and awareness of the context in which they were presented, including the various cultural tendencies active in this arena after the triumph of the Revolution.

Needed today are new readings of Fidel’s “Words,” and awareness of the context in which they were presented, including the various cultural tendencies active in this arena after the triumph of the Revolution.

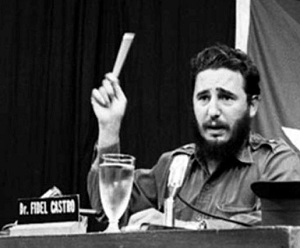

The passage of time requires new readings of Fidel’s “Words to Intellectuals.”e than a few members of younger generations are not familiar with this memorable speech by the leader of the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro, delivered on June 30, 1961 at the National Library, or the circumstances in which it was presented, after many hours of conversation between the country’s leadership and representatives of Cuba’s artistic and intellectual vanguard, on the 16th and the 23rd. “Within the revolution everything, against the revolution nothing,” is the phrase that is recalled, in many cases, as the only reference to the historic comment.

Unfortunately, his other remarks have not been published, in particular those he made on the 16th and 23rd, which provide insight into the context in which Fidel presented his “Words…” which were not a speech properly speaking, but a commentary constructed from the notes he made as he patiently listened to the rest of the participants, making only brief inquiries and occasionally interupting. Many eyewitnesses, however, left to posterity their memories of the meeting and the audio of Fidel’s words is also preserved, allowing us to appreciate the climate of the event and the tone he used.

The meeting was triggered by the prohibition of screenings of the documentary PM (Past Meridian). Although the short 14-minute film had been broadcast on Cuban television, on a Monday early in the month of May, its presentation in the country’s movie theaters was canceled after Alfredo Guevara, as president of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (Icaic), informed Edith Garcia Buchaca, secretary of the National Council of Culture, that Icaic’s Commission for the Study and Classification of Films was opposed to its massive screening.

The film, by Orlando Jimenez and Sabá Cabrera Infante, featured the extravagant nightly entertainment enjoyed by a portion of the population in Havana’s bars and nightclubs, a seemingly inconsequential topic in today’s light, but that in the context of 1961, when the country was mobilized and facing constant imperialist attacks, could lend itself to other readings, as in fact it did. The documentary, although it did not fail to garner praise and positive reviews from critics, was questioned as extemporaneous and harmful to the interests of the Cuban people and its Revolution.

In view of the disagreements that arose with the censoring of the film, a meeting was called with a group of artists and writers on May 31 at the Casa de las Americas, but after a heated discussion, no definitive conclusions were reached. It was proposed that the film be analyzed by mass organizations and that the population would have the last word, but the consultation did not take place. On June 2, the newspaper Hoy published the decision made by Icaic’s Commission for the Study and Classification of Films, making the atmosphere even more tense. Guillermo Cabrera Infante wrote a letter of protest to Nicolás Guillén, president of the Association of Writers and Artists. It then became necessary to postpone the Congress of Writers and Artists that was being prepared, and Prime Minister Fidel Castro asked the National Council of Culture to convene a broad meeting with artists and intellectuals in which all tendencies would be present.

Beyond censorship of the documentary PM, which served as a catalyst, more fundamental issues were circulating within the environment, which urgently needed to be addressed by the leadership of the Revolution – especially the issue of forging unity within the Cuban artistic and intellectual movement and incorporating this process within the dialogue that was already underway between other sectors of society and the forces that had led the struggle against the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. This would be one of the most immediate accomplishments of the meetings at the National Library: The successful first Congress of Writers and Artists which led to the founding of the Union of Cuban Writers and Artists (Uneac), with national poet Nicolás Guillén as its first president, in August of the same year.

A few months later, the cultural supplements Lunes and Hoy Domingo, in the newpaper Revolución, were dropped, opening the way for the journal Unión and the magazine La Gaceta de Cuba, both published by Uneac.

Fidel was fully aware that an internal struggle was sharpening for control of the country’s cultural apparatus, between tendencies with different and even conflicting positions on the relationship between politics and culture, thus posing the immediate challenge of intervening to settle the disagreements without favoring one group over another, in order to clearly define a position, not in relation to what occurred around the documentary, but rather the path the Revolution should take in terms of cultural policy.

The mapping of tendencies and groups with different perspectives and visions of the relationship between state power and culture is a very complex task, but, at the risk of oversimplifying, they can be grouped into two large blocs. One group was centered around Revolución’s cultural supplement and Carlos Franqui – who had been expelled from the Popular Socialist Party (PSP), originally the Communist Party of Cuba, before joining the July 26th Movement, and, in addition to several television stations, directed the newspaper Revolución, the official voice of the July 26th Movement, which beginning in March of 1959, published Lunes, edited by Guillermo Cabrera Infante.

This group defended a militant commitment to the Revolution on the part of artists, but also political non-interference in cultural affairs and freedom without class-based or ideological formulations. They maintained a critical position toward figures they considered decadent representatives of the cultural past and the old generation, which led them to commit sectarian errors, publishing unnecessary attacks on artists and intellectuals essential to the national culture, including: José Lezama Lima, Cintio Vitier, Samuel Feijóo, Alejo Carpentier and Alicia Alonso, which far from contributing to the creation of an intergenerational bloc in support of the revolutionary process, led to the development of an unproductive generation gap and undermined unity on the cultural front.

Members of this group also published more than a few sharp criticisms of the PSP in the supplement, emphasizing its past mistakes, contrary to the goal of the Revolution’s leadership to overcome previous errors and unite the principal political forces that had fought against the Batista dictatorship, with a view toward the future.

They frequently insisted on incorporating more of the international legacy into Cuban culture, as well as experimentation and the incessant search for new paths in art. They spoke out against any hint of Stalinism, but some used this position to mask their deep anti-communism. The PM incident served as a pretext for some members of the group to incite unfounded fears that the excesses of the USSR against creators would be repeated in Cuba. Nonetheless, Revolución Lunes, as a printed publication, left an important historical legacy, recording the pulse of national and international cultural events of the time and conducted valuable informative work.

Another group, generally speaking, held a Marxist-Leninist position emphasizing political commitment, although subtle but significant differences existed among members regarding the relationship between art and politics. Included in this group were outstanding figures like Alfredo Guevara, Edith García Buchaca and Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, from the Hoy newspaper and its Sunday cultural magazine: Hoy Domingo. Within this group, and especially the editors of Hoy, the recovery and re-evaluation of Cuba’s cultural past was considered a strength in the battle against U.S. imperialism, but some of its members clearly assumed or approached the tenets of “socialist realism” to promote these objectives. Of course, at the level of individuals, ideological positions were more varied.

(Taken from Granma)