Fidel’s “Words to the intellectuals” in 1961 forged consensus among the country’s artists and intellectuals, another great victory against internal enemies, sectarianism, intolerance and dogmatism.

Fidel’s “Words to the intellectuals” in 1961 forged consensus among the country’s artists and intellectuals, another great victory against internal enemies, sectarianism, intolerance and dogmatism.

I admire the consistency between Fidel’s words, his actions and the subsequent work of the Revolution – the possibilities Cuba has created for the development of artists and intellectuals.

One must struggle and win, one must live and love,

One must laugh and dance, one must die and create. Sara Gonzalez

If it were only a picture, it would not be worth the effort, photos fade in time, but those of us who did not live the moment are not told enough. This is why I have listened to and read, several times, the speech Fidel delivered in June of 1961, at the National Library, which has gone down in history as his “Words to Intellectuals.”

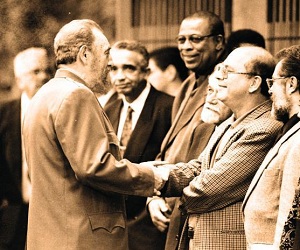

Sixty years later, I imagine that young man without the imposition of protocols of a bourgeois diplomacy, speaking casually to a large audience, full of young people like himself, as well as artists and intellectuals who saw the triumph of the Revolution arrive with long, well-established careers.

What triumphed in Cuba in 1959 was, above of all, a cultural revolution. We know that culture is not only artistic-literary creation, with much more than a cognitive dimension. Culture is the DNA of a society, its representations, its practices; its aspirations are the motivations of its subjects. Culture is the ethics of a process.

When the Revolution assumed government power, a struggle between the past and the present arose in Cuba over the construction of a different reality, a culture to uproot preconceived lifestyles, ways of understanding and functioning in society; to demystify the customs and supposed good practices based on oppressive laws, controlling an active subject who understands what is established as the only possible reality.

This is how Revolution became synonymous with sovereignty, because the ethics of an underdeveloped island, without industrialization, economically and culturally dependent on another government, is subjected to the globalization of its basic practices, with a mixed identity openly moving toward annexation.

Within the homeland everything, against the homeland nothing; and at the same time, homeland is synonymous with the people.

Imagining the sociological plane of the time, without decontextualizing, I listen to Fidel’s voice, without renouncing my own subjectivity as an artist, because no one lives devoid of passions, not even the speaker who recognizes it in his own “Words.”

What I have learned in reviewing his speech is very personal, experience and knowledge influence the way we receive a message. Nevertheless, there were clear principles in Fidel’s speech to his contemporaries, the first of which is to recognize that a revolution, like the work of any artist, is not made for future generations; a revolution becomes posterity when it is made by and for the men and women of the present.

The current generation needs its own natural epic, its own words; what now seems obsolete must be re-thought, in order to remain loyal to the sense of the historical moment evident in every sentence Fidel spoke in June of 1961.

“Words to the Intellectuals” set the stage for what would become Cuban cultural policy, but it did not impose formulas for methods. Fidel proclaimed the right of a revolution to defend itself when it has emerged of necessity and the will of a people, although that does not mean that the government, acting on behalf of the people and within the law, is infallible.

The Revolution’s practice in the years following Fidel’s speech confirmed its commitment to defend freedoms, to facilitate the free exercise of creation for artists, and the means, moreover, to do so.

The Union of Cuban Writers and Artists (Uneac), founded in August of 1961, was itself a product of discussions between artists and the highest state authorities. It gave shape to the natural association of creators, bringing them together to address the problematic issues involved in making art. The organization served to facilitate permanent dialogue between the artistic community and institutions implementing the country’s cultural policy.

When, during a gray five-year period, political fanaticism and the misinterpretation of ideas took their toll on the personal lives of some artists and the ghost of defined parameters mutilated their work, lessons were also learned. In the first place, the damage that can be done by power in the hands of a bureaucrat was confirmed, but loyalty was strengthened as well, among artists who understood that censorship, persecution and immoral attempts to discredit others are anathema to revolutionaries, practices befitting only opportunists and cowards.

The Revolution never remained static; the Ministry of Culture was created to replace an ineffective entity given the new reality of Cuban art and intellectuality and, progressively, progress was made in efforts to ensure that artists had opportunities to debate, express constructive criticism and real participation in the decisions and processes related to their work.

Today, in the 21st century, I admire, more than anything, the consistency between Fidel’s words, his actions and the subsequent work of the Revolution – the spaces and possibilities that Cuba has created for the development of artists and intellectuals, the organizations in which we meet and the President of the Republic’s support of free, emancipatory art.

Nonetheless, many of the challenges of the present are much the same as the first Cuba faced. Cultural institutions cannot let discussions be repeated without finding solutions to problems, or at least making visible the work underway to solve them, and addressing not only issues in the realm of material needs and services, but especially on the qualitative and moral plane.

No just struggle can be manipulated for reactionary purposes. Artists’ organizations must keep criticism alive and subordinate themselves to the members they represent, along with the commitment to develop and promote vanguard art to expand the population’s ability to discriminate and appreciate, to contribute to the spiritual growth and human fulfillment of Cubans.

In revolutions everything happens at the same time. During Fidel’s 1961 meeting with artists and intellectuals in the National Library, echoes could be heard of mercenary shrapnel in Playa Giron, of the songs and mourning of our first victory. “Words to the intellectuals” forged consensus among the country’s artists and intellectuals, another great victory against internal enemies, sectarianism, dogma, intolerance and political fundamentalism.

In June of 1961, a revolutionary pact was established, based on a lucid understanding of the role of art, not as propaganda for a particular political line, but as service to the people. Its virtues continue to lie in consistency and coherence, in everyone doing their part, and doing it well, fulfilling the commitment we have made to society. Morality and truth are a bare wall against which any speculation fails.

(Taken from Granma)