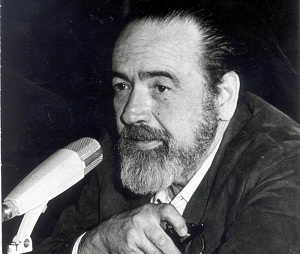

July 2, 1920, was a great day for Cuba: one of the greatest poets in our history was born. Eliseo Diego was to have a peaceful childhood in his native Havana, and would grow up to become what he is, a key figure in Cuban letters, Latin American letters, and the Spanish language.

July 2, 1920, was a great day for Cuba: one of the greatest poets in our history was born. Eliseo Diego was to have a peaceful childhood in his native Havana, and would grow up to become what he is, a key figure in Cuban letters, Latin American letters, and the Spanish language.

He began his narrative work with En las oscuras manos del olvido (1942), when he was already a member of the famous staff at the magazine Orígenes, led by its most outstanding figure, José Lezama Lima, who saluted the book for its pristine, orderly prose, of real beauty, typical of the man who would offer, only a few years later in his biological youth, an essential work of Cuban poetry: En la Calzada de Jesús del Monte (1949), which continues to delight and teach. It is a pleasure to begin with the syllables of the first verse: “On the rather enormous road of Jesus del Monte ….” As if we are being introduced to a fairy tale, to continue: “Where too much light forms other walls with the dust, tires my principal habit of remembering a name…” This book became legendary. One of the streets of Havana, today called 10 de Octubre, earned the privilege of an ode, an anthem to its populous existence.

Eliseo never stopped writing excellent prose, full of surprises in every exact brushstroke, like his poetry. Divertimentos (1946) was his second book of short stories, as were Versiones (poetic prose) (1970) and Noticias de la Quimera) (1975), to once again seduce us with his expressive grace. But poetry was his most royal preserve, with unique resonances. A poet of detail, his work is naming things according to their intimacies, with the meticulous intention of bringing things to life in his verses. Eliseo Diego is the greatest minimalist poet in Cuba, capable of stopping at the minimum to appreciate the immensity of the universe.

The sequence of his books of poetry show implicit poetics that take into account levity, life and death, the urban landscape, the deep sense of Cuban identity, the homeland, love, family and faith. They are: Por los extraños pueblos (1958), El oscuro esplendor (1966), Muestrario del mundo o Libro de las maravillas de Boloña (1967), Los días de tu vida (1977), A través de mi espejo (1981), Inventario de asombros (1982), Cuatro de Oros (1990). He published all of these works during his lifetime, along with his volume of essays Libro de quizás y de quién sabe (1989). Appearing after his death in 1994, under the loving care of his daughter Josefina de Diego, were En otro reino frágil (1999), Aquí he vivido (2000) and Poemas al margen (2000), among others.

Cuatro de oros seems to play with a deck of cards, or perhaps evoke his wife and three children: this is Eliseo’s poetry, subtle, with double readings suggested amid games of images. His work never becomes inaccessible, and, as he often referred to reminiscences of his childhood, it was not unusual for him to publish Soñar despierto (1988), illustrated by his son Rapi Diego, in which he reminds us, among other poems for children, of the playful experiences of happy years: “You alone and the wind of strange whistles, such are the games of hide-and-seek.” Eliseo knew how to show us the transcendent value of what seems ephemeral and the human need for poetry.

As a poet from Orígenes, he shared with his fellow writers there many points of poetic perception, such as viewing the countryside from historical and urban points of view, the static nature of parks and small towns, the idea of a Cuban tradition that starts with household customs, meals, family conversations, childish whispers, rooms. It is an intimacy that emerges from this domestic setting to define the life of a community through what we call “lo cubano”. There is his closeness to the master José Lezama Lima, not in the extravagance of baroque language, but in the essence of capturing the peculiarity of being Cuban, the popular vision of Fina García Marruz, or the parks of Cleva Solís. He shares the subtle view of a Cintio Vitier and the cultured reach of a Gaston Baquero, but also the splendor of the insular nature, so evident in Samuel Feijóo’s work.

Eliseo Diego, alive is in his work, is not a solitary poet. He participates in an ensemble, a generational one that observed objective reality and from it extracted subjectivity in pristine poetry, delicate and at the same time resistant: resistance to time, that which in his poem Testamento he left us as an inheritance: “I leave you time, all time.” If I were to recommend to readers a brief selection of his poems, among them would be: El primer discurso, Voy a nombrar las cosas, Lamentaciones, En el pueblo perdido, Con un gesto, Entre las aguas, La noche, Oro, Oda a la joven luz, Cristóbal Colón inventa el Nuevo Mundo, Pequeña historia de Cuba, titles from the best Cuban poetry of all time.

Eliseo Diego was a great connoisseur of English-language literary works, from which he translated several texts, especially poetry, but he was also attentive to literature for children. After the triumph of the Revolution, he worked continuously on various tasks of the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba, as one of its founders. In 1986 he received the National Prize for Literature and in 1993 the Juan Rulfo International Prize for Latin American and Caribbean Literature. He won many other awards and published his Prosas escogidas in 1983.

The great poet has now reached his centenary. As a matter of honor, Cuba cannot let the date pass without the necessary tribute to someone who honors us with the quality of his work, for someone who with his keen eye told us: “Light, in my country resists memory, as gold resists the sweat of greed, endures within itself, ignores us, in its indifferent being, its transparency.”

(Source: Granma)