Surely no one thought of death in the Dos Rios camp on that busy morning of May 19, 1895. It is likely that the night before Martí interrupted the letter he was writing to Manuel Mercado when Bartolomé Masó arrived with his cavalry troops from Manzanilllo, who then continued on to the Vuelta Grande camp to give the horses a rest.

Surely no one thought of death in the Dos Rios camp on that busy morning of May 19, 1895. It is likely that the night before Martí interrupted the letter he was writing to Manuel Mercado when Bartolomé Masó arrived with his cavalry troops from Manzanilllo, who then continued on to the Vuelta Grande camp to give the horses a rest.

The meeting with this patriot who, with two of his brothers, had seconded Céspedes on October 10, was an essential participant in the organization and direction of the war, since Masó, beyond being an independence leader in his native region, provided continuity, linking this war with the revolution’s first battle in Yara, as Martí had written weeks before in the Montecristi Manifesto.

That is why, very early, before going to La Vuelta Grande, Martí wrote what would be his last text: a note to Máximo Gómez informing him of Masó’s arrival. The General in Chief joined them shortly after noon. And while the meal was being prepared, Masó, Gómez and Martí spoke with the Mambi troops. There was patriotic reverence, joy, cheers for the leaders. This was Martí’s fourth and last Mambi speech. Gómez recalls the event in his Campaign Diary: “We experienced a moment of true enthusiasm. The troops were excited and Martí spoke with true ardor and the spirit of a warrior…” As the gathering was about to end, they learned that the enemy was nearby and, in a furious avalanche, all jumped into the saddle to attack – the orator among them.

During those weeks in the Cuban east, Marti’s leadership reached its highest expression. His path to this moment had begun when he returned to Cuba in 1878. He joined those conspiring against colonialism and was elected, the following year, as vice president of a Central Revolutionary Club in Havana to lead work on the island. He was deported to Spain but escaped in 1880, to meet with General Calixto García in New York, who recognized his ability. When the General departed to Cuba, he left Martí as temporary head of the Revolutionary Committee that, from that city, directed the ongoing “Little War.”

Thus, Marti’s leadership became apparent, along with his abilities as an organizer and mobilize, using his pen and oratory. He was developing and offering new perspectives in the fight against colonialism. From then on, he established two essential precepts: The new revolution would not emerge from anger, but from reflection; and the people, “the suffering masses”, were the true leaders of revolutions. Thus, the fight for freedom must follow a plan, a project, an organization, with a social base of the great majority.

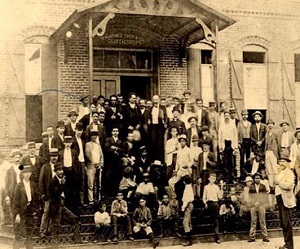

During the following years, despite the failures in restarting the fight for freedom, Martí formed an active group of followers in New York and captured the hearts of emigrants in other parts of the United States, particularly workers in Florida. When he founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party (PRC) in 1892, his influence was felt by emigrants in Central America, across the Caribbean and even Europe.

The secret of his success in building unity – overcoming the mistrust of the established leaders and figures, as well as personal and group jealousies based on region, social sectors and generations – was precisely in making use of a modern political organization, a Party, in which branches had autonomy in practical action, and democratically elected its basic, non-bureaucratic leadership. The Party’s program established the elements required for a fully sovereign republic, social justice for the people, and solidarity with the Puerto Rican struggle for independence.

Elected every year as a PRC delegate, Martí became the émigré community’s leader, whose dedication and financial resources allowed him to acquire the essentials for the armed struggle, the only option remaining given the intransigence of Spanish colonialism exploiting the island.

Marti’s ideas, expressed in the newspaper Patria, in his numerous speeches, in Party documents, in his voluminous correspondence, explain his rise as a leader outside Cuba. But he was also, increasingly, the leader of those involved in the conspiracy within the country.

His words everywhere promoted the necessary war, a war of love, not hatred, quick as lightning to avoid the interference of the northern power; the war of republican spirit, alien to the leadership of individual strongmen; the war that the republic needed, with all and for the good of all, that would open the country to all justice for black Cubans, for campesinos, workers, for Spanish immigrants; the war to unite the peoples of our America in action and thus prevent their domination by nascent U.S. monopolies, the American Rome, as he said.

His oratory was fierce only when the homeland or the dignity of the Cuban people were attacked. He never resorted to insults, coarse words, defiance or irrational fury. He fought ferociously against ideas, more than against people. He convinced others with his words and deeds. He handled the revolution’s funds with absolute honesty. He preached by way of example in daily life, as well as his words. He insisted on creating, on being original, on thinking about our problems, without ignoring the rest of the world, but adapting whatever was useful to our needs.

He had a highly developed sense of duty and insisted on participating in the war. This was a leader’s commitment to his people; he should accompany the fighters and ensure that the principles of the revolution were upheld and practiced, to ensure that the colony did not persist within the republic and prevent the greatest danger: domination by the United States.

He said it often: Once the war began, the patriotic leadership would take up residence on the island. That is why he landed on Playita de Cajobabo, April 11, with a small group, which could well have drowned, but marched on despite enemy persecution.

And after joining the Cuban troops he worked hard for exhausting days in the scrub and mountains: writing letters and documents to organize and structure the war, building unity around the idea of providing the revolution effective institutionalization, which would overcome the divisions of ’68; conversations with commanders and officers, with the soldiers and the wounded to understand their ideas and desires, as one more comrade and as the leader who did not separate himself from his people.

Mutual respect and admiration were established between Martí and Gómez, during those weeks. The decision of the General in Chief, in the Council of Chiefs, to grant Martí the rank of Major General gave him a voice within the military: Martí was no longer just the PRC delegate; his authority was increased and he became a political and military leader. The soldiers heard him and cheered him on the four occasions he spoke in the camps, demonstrating how they welcomed him as the leader of his people, not only Cubans abroad, on several occasions calling out to him as President, while he spoke.

Days before his departure to Cuba, in a farewell letter to his Dominican friend Federico Henríquez y Carvajal, on March 25, he stated: “I called for the war: my responsibility begins with it, not ending it. For me the homeland will never be a triumph, but rather agony and a duty.”

The person who expressed his understanding of the duty imposed by his position as delegate was the same person who, after declaring to Manuel Mercado his great anti-imperialist objective, recalled his responsibility: “This way, I do my duty.”

On that May 19, the soldier José Martí went to battle, gun in hand, as he had evoked in his speech to the troops moments before. This was not an irresponsible act, much less a suicide: the military officer, the delegate, the leader, the Mambí, went to do his duty in Dos Ríos. That is why he is and will be the Master and Apostle, the one who teaches, who explains, who guides.

(Source: Granma)