By Flor de Paz

This Friday, August 26, Hugo Rius Blein, José Martí National Journalism Award winner for his life’s work, passed away. The interview that follows is just over five years old. From it emerged (and vice versa) a television capsule that we have placed at the end of the text. With it, the Union of Cuban Journalists remembers his life and his dedication to journalism.

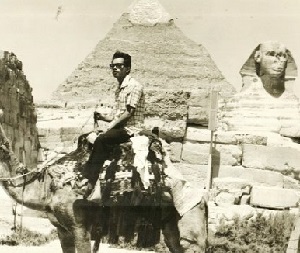

There is a photo in which Hugo Felipe Rius Blein is mounted on a camel, in front of the Great Sphinx of one of the pyramids of Giza, in Egypt. In 1953, exactly ten years before the moment he records the snapshot, he had contemplated them through a View-Master (3D slide viewer) that the wise men had “brought” to him. But the contraption came alone, without any of those cardboard discs and little windows through which the transparent images peeked out. To buy the first one, he scraped together 50 cents, coin by coin. And in a little store, located in San José between Galiano and Águila, in the heart of Havana at the time, he chose the “compact” of Egyptian landscapes. Prenuncio or luck? For Rius Blein, the initial assignment that they made him in Prensa Latina: to be a correspondent for the Agency in the mythical country of Northwest Africa.

“I wished for it, but it was life that took me there.” And if you go to Cairo, you have to go see the pyramids and ride a camel.

Hugo was born on August 23, 1940 in the Havana neighborhood of Luyanó, where he also became an adult. From his father, Ramón, a tobacco shop reader, of Catalan descent, he inherited a surname (it means rivers) with which he has little luck being spelled correctly. The legacy of her mother, Mercedes, a destemmer by trade who devoted herself to caring for her children at home, is a variation of the original Bleu. She was the granddaughter of a 19th century free-belly black woman who adopted the Blen (wrong) from her owners. And later, when Hugo, the second of a progeny of two, took out his birth registration for the first time, he knew that they had written him down as Blein, and he stayed with him. Ramón and Mercedes had offspring between the fourth and fifth decade of their lives, “they were very humble people and they gave me a lot of love.”

—Runs in my veins black blood, Chinese coolies[i] and Catalan. My maternal grandmother was a mixture of black and Chinese.

When he was able to read and write, it was the most important moment of Hugo’s childhood. “Because without being literate you don’t know the world, you don’t know life, you’re not going to grow up”. Later, he especially remembers his birthday days, because of his parents’ efforts to make him feel flattered, happy; and Christmas Eve and waiting for the new year, hours in which the family gathered around a table seized by attachment and simplicity.

From adolescence, he does not forget that he was the best record of the course in high school. This condition allowed him to win a scholarship and prepare to enter the Normal School for Teachers, at a time when he also managed to compartmentalize studies with the Márquez Sterling Professional School of Journalism. Later, at the age of 29, he graduated, and after a long period in teaching journalism, Full Professor and Master in Communication Sciences. Because he has always been a teacher and journalist.

His vocation for journalism? It comes from the job of Ramón, his father, who came home every day with a mountain of newspapers and a red and blue pencil to mark what he considered important to communicate to the cigar workers. Little Hugo accompanied him and lived this daily exercise intensely. Thus was born in him a feeling of appreciation for the paper, for the purpose of transmitting news.

—I perceived that newspapers were very important, like food and water.

An article in which he fought for Cuba to have a national merchant marine, in a mimeographed newspaper that he did in the Superior School was his first journalistic adventure; he was fourteen or fifteen years old. In the Normal, he created the student Horizonte, which only reached one or two runs. During his time at Márquez Sterling he also produced a small newspaper, until he collaborated with the real ones: Hoy, El Mundo, Revolución, Juventud Rebelde and Granma.

During the last years of the 50s, and as part of the masonic youth (Association of Young Hope of the Fraternity), Hugo was linked with some brothers, “which is what we called him then” incorporated into the Movement 26 of July. And so he performed some tasks in the field of propaganda; among them, sending proclamations to Batista’s military in which they were warned that the tyranny was not going to last long, that they take a social position in life. Also, he went to the houses of some members of the underground in the provinces who had had to flee, to inform their relatives about them and collect clothes and other items that they had left behind.

—The same way I brought food to the prisoners of the Prince’s Castle, of my own lodge, where the possible money was collected. They are the small tasks that I fulfilled in the fight against tyranny, small in my opinion, but with a lot of commitment.

…

He is almost 78 years old and has dedicated his life to journalism. He remembers his beginnings, in 1962, at the Agencia Prensa Latina (PL), with a sustained gaze and reflective cadence. “Then it was still a journalist project, because he was only 22.” And so, based on decades of professional experience, he usually explains to his students of the optional subject International Journalism, that even at thirty years old one is barely a promise and at forty is when one knows if one really is a journalist.

—Without ruling out precocity. But if precocity does not assume a fundamental value: humility, they can be lost along the way.

That is why he describes his work as PL’s correspondent in Egypt as premature, barely a year after joining the Agency; although he is proud of having put all his will and knowledge into this task to do the job to the best of his ability.

Egypt was a privilege for me. It gave me great opportunities, like covering the founding of what is now the African Union, then the Organization of African Unity. His first conference was in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

“I was able to make it to the royal palace and meet and greet then-legendary Emperor Haile Selassie; the real character of The Emperor, by Ryszard Kapuscinski. I was at the entrance of the palace where Selassie used to have a live lion chained to a tree. Even Rius Blein coincided in Ethiopia with the Polish journalist and witnessed some of the scenes that he narrates in his work. “And now I am passionate about Kapuscinski’s books.”

It is around three in the afternoon on February 4, 2018. The set of the interview is Hugo’s real work space in her apartment on Calle Línea, in which the audiovisual director has barely made any changes before to film. An art deco style bureau, in front of a huge wood and glass bookcase, identifies the place set with plants, framed photos and diplomas, writing devices, small figures carved in precious African woods and other bookcases and tables, one of them for the computer and dissimilar devices associated with the digital age.

Rius Blein speaks slowly and in a low voice, without moving his hands too much. He is not disturbed by the cameras that focus on him. He does not miss the rhythm of the speech. He doesn’t smile. He maintains the tone of someone who owns a great fortune: the quarries of human culture to which he has been able to access, immersed as he was always in the routines of the worlds he knew to try to catch them in his learning; or also in the sources of reading. “Just like Ulysses on his trip to Ithaca. He arrived without material wealth, but he has the wealth of experiences. They are footprints that stay with you forever.

During the interview, Hugo thanks his wife, María del Carmen Marín, with whom he has two children, for everything he has achieved in his profession; for the tranquility with which he has been able to do it, for the love and patience that he has had for her. “This work often implies a share of neglect and renunciation of family enjoyment, in pursuit of an informative task. We have been together in all correspondents; she has been involved in the work and she has also known those other worlds.”

…

In Algeria, its destination after Egypt, the PL correspondent was located in an old house with Moorish architecture, which had been the headquarters of the OAS (the terrorist group that tried to prevent that country’s independence), thanks to the help of the first president Ahmed Ben Bella. There, one night, Che appeared with the Cuban ambassador, who was Commander Serguera. And this is another of Hugo’s stories.

—I was a second journalist, learning from Gabriel Molina Franchossi, an important figure in Cuban journalism. Photography obsessed me at that time, to the point that I would spend hours in a room-studio developing, in addition to doing my work as a correspondent. As a photographer I was the only one who covered that second visit of Che to the North African nation. The images I took were also the only ones published by Algerian newspapers. So, that night Molina decided to show them to Che. He checked them very carefully, and suddenly asked:

“Who made them?”

I answered, and he told me:

—Better dedicate yourself to studying economics.

That hit me like a bucket of cold water, but he immediately clarified:

—It’s just that I’m very fat; It’s not the photographer’s fault.

Some time later I discovered that in the background of his comment was the disagreement with his physique, facing the guerrilla projects that he was already nesting.

As part of that conversation, Che also told Rius about the time he used to take photos in Mexico’s Zócalo. “People passed by and he photographed them. In addition, he sold little virgins of Guadalupe. And I, in my innocence of age, told him that he lost if he threw away the photo and then they didn’t want to buy it. And he replied mischievously:

— And you think I’m stupid? First I pretended to throw away the photo, and if they picked up the piece of paper I told them, wait, I’m going to take a better one for you, and that’s when I really threw it away.

“Molina and I had worried about making a small library on Africa in a corner of that house in Addis Ababa; Che discovered it and went crazy with the books we had. And of course he ransacked the shelf for us.”

…

In the scaffolding of his stories, Rius Blein places the time and space of his existence, substantiated by events of universal value that he has witnessed, and by the diversity of human ways of living appreciated in much of the planet, but especially on the African continent.

The First Congress of the ANC and the election of Nelson Mandela as president of South Africa, is one of the events that he places among his significant emotions. “It was the first time that he went to the apartheid country and, furthermore, at the time that the ANC was no longer clandestine, he already had a formal citizenship card, because he always had a real one. And seeing that giant of history that was Nelson Mandela emerge up close, in a South Africa without apartheid, is a lesson in what it means to believe in a cause regardless of the sacrifice, the hardships. If you believe in it, you can achieve the sacred goal.”

From Ethiopia, he admires the kindness, affection and loyalty of that people with the Cubans. “At first I was crushed by the misery I found; but later, I got to know the nature of the Ethiopians, the respect they have for hierarchies, not only formal but also intellectual and human”. And that was the country where he most enjoyed professional accomplishments.

In addition to the founding of the African Union, Ethiopia, one of the oldest countries in the world, experienced the revolution led by Mengistu, Fidel’s visit, significant solidarity conferences and, finally, the arrival of the rebels when Mengistu fled and the country entered a situation of great violence and danger.

—Before that moment, there was an attempted coup and I was able to be the first to break the news. When my colleagues decided to say it, their communications had already been closed. I knew what happened through a boy who sold candy and chewing gum, whom I always bought to help him. We were near the Ministry of Defense and I asked him in Amharic: what’s going on? He, in his poor English, told me that they had killed the Minister of Defense. And indeed, they had killed him. That is why all sources must be respected.

Also in Ethiopia, he witnessed the extraordinary work of Cuban doctors, the presence of fighters from the island on the border and his contribution to defending the integrity of the country against the aggression of Somalia.

—That’s when they arrest Cardoso Villavicencio and take him to Somalia.

And in 1988, when the combatant’s long solitary captivity was broken, Hugo Rius was one of the first two Cuban reporters to receive him at the foot of the steps of an airplane upon his arrival at the Ethiopian Dire Dawa airport.

But Rius’s bond with Ethiopia is so deep that even he had the misfortune of closing the PL office in Addis Ababa, when the Agency went into crisis in the 1990s, due to the economic problems Cuba suffered. So he moved to Zimbabwe.

—It hurt me so much that, years later, when there was talk of reopening offices in several countries, I said: if they ask for a correspondent for Ethiopia, I’ll leave with what I’m wearing. At that time I was in the UN (2000-2005), and the people there did not believe me. But the idea of going back to the country in the Horn of Africa was more valuable to me than staying at the United Nations, without letting me stop thinking that it was also important.

At the UN, he had to cover dramatic and significant events such as the invasion of Iraq in 2003, and Cuba’s resounding victories in the votes against the United States blockade, and he also had to move in the host city within the restricted 25 miles, under the very hostile government of Bush Jr.

…

To exercise journalism, Rius has had the good fortune to be in various media. For Prensa Latina, he was a correspondent in Egypt, in Algeria; in Ethiopia, for the horn of Africa; in Zimbabwe, for Southern Africa, and at the UN and in Vietnam. He is now the editor of the PL English website.

“The Agency has given me the charm of immediacy. A spell that gravitates towards achieving, in a short time, the precise text; dense and brief at the same time. And those are also his challenges.

PL, where he has been for two stages (1962-65 and 1988 to date), opened doors to realities such as wars, conflicts, coups, calamities. By the way, he recalls an anecdote from the 19th century, by Henry Morton Stanley (a journalist for British and American publications), which he captured in his book The Search for Dr. Livingstone: Journey to the Middle of Africa. This great explorer had been lost for two years and was finally found by Stanley north of Lake Tanganyika. The man went with his arsenal of questions, and before he could ask the first, Livingstone told him: ‘Tell me, journalist, what’s going on in the world?’

—Well, that’s what a journalist on international affairs or from an agency like PL does. That is to say, he builds the “Imago world”, he says what happens, because the world is no longer wide and alien, now it is narrow and his own, thanks to the development of new communications technologies.

Through Bohemia (1972-87), Hugo Rius experiences a deep feeling of closeness. “It was the medium that trained me to write my books[ii], by having the possibility of recreating what happened, because it is a publication that is not limited to punctual, immediate information. So, you can play with literature a bit, make a bit of literature. There, I matured, grew up and felt very fulfilled professionally. I was also a writer specializing in Africa and the Middle East, chief information officer and deputy director”

As a special correspondent for the magazine, he covered the ECLAC conference in Guatemala and the UN General Assembly in 1977; Fidel’s visit to Ethiopia and Cozumel, and the first steps in the process of change in the country on the eastern end of Africa, in 1978. He toured Yemen, Tanzania, Mozambique, Angola and Benin, where he reported on Cuban internationalist work on different fronts. In Angola, he traveled with joint FAPLA and FAR troops to the Quibala-Eboe, Ambriz-Ambrizete fronts until the fall of Santo Antonio do Zaire, with the forces of the Cuban commander Zayas and the similar Angolan Antonio Dos Santos (N ´Give it). He was also in Benguela and Huambo. Based in Luanda, he accompanied President Neto to Santo Tomas and Principe as a journalist. And he toured Afghanistan at a time of clashes between a progressive government and the CIA-armed Taliban.

…

Vietnam was for Rius a pending issue. Because in 1965 he had a lapse in his journalistic work, he worked at the Cuban Institute of Friendship with the Peoples as a French language guide, and later he was director of Afroasia there.

— I was part of the organization of the Tricontinental Conference in 1966, and then we were very concerned with Vietnam, with the entire solidarity movement that was generated. I wanted to go to Vietnam, what Cuban doesn’t want to go?

But the invitation came to him at a time when he was in Poland. The then President Jaruzelski had given him an interview, and he was unable to go to Vietnam. Until in 2011 he had the opportunity to visit the country he imagined: that of the Vietnamese walking through the streets with their sticks and a load of fruit, a very impoverished country.

—It was very surprising to see how in such a short time it had become a nation of medium consumption, according to the UN classification. That is, they raised the industry and take advantage of technology.

“They have solved the fundamental problems: food, clothing, transportation, and around the difficulties with housing, they have looked for alternatives, due to the little space they have left to develop. So, at every turn, I experienced a mixture of blue envy and shame. Because I think: Caramba, we were helping this people that was made of land and when they finally defeated the North Americans in ’75 there was a poverty level of fifty-nine percent, they had to import rice to eat, they had nothing . However, today they donate the rice to us, and the coffee also comes from there!”

…

Hugo Rius Blein, in 1970, gave Salvador Allende the first telephone interview for Cuban radio. After much insistence, the newly elected president answered the call.

— He spoke to me about what his victory meant on the third occasion that he was running, about the need to make changes in Chile. And it was obvious that he was very besieged by the press and by many people.

Rius’s journalistic career was then in a germinal phase and it was the most intense stage of his work on radio and television (1967-1972), when he also wrote scripts for the audiovisuals of the Teatro Testimonio program, which dramatized Latin American conflicts. At the same time, he made comments on Radio Rebelde, without disdaining that, during the 10 million harvest, he was a reporter and director of Radio Reloj, nor that he was an international commentator for NTV and the current affairs roundtables at the time.

From his current journalistic activity, La Coletilla highlights his contribution to Cubadebate. Rosa Miriam Elizalde involved him, and “it has been a pleasure to write various articles for that space, since “it is the most conceptually and practically advanced Cuban media.” However, he does not omit his exercise as an opinion columnist in Juventud Rebelde, and more recently in Granma.

Now, Hugo Rius Blein has many completed works and not a few in the pipeline; he has the respect of his colleagues and his students (especially when they call him Kapuscinski behind his back); he has life to live; He has children; has grandchildren; he has María del Carmen, he has journalism!

— Journalism?: Capturing the essences of life. Because without looking for the essence of what you are reporting, without transmitting a breath of guidance or at least a mobilizing breath of other people’s thinking, you cannot speak of journalism. Journalism is to contribute to the mobilization of other people’s intelligence, of human cognition.