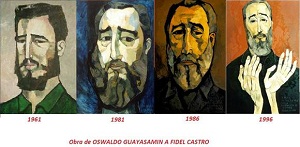

Guayasamín’s paintings of Fidel reach their 55th, 35th, 30th and 20th anniversaries

Guayasamín’s paintings of Fidel reach their 55th, 35th, 30th and 20th anniversaries

“I am always going to return. Keeping a light lit.”

(Oswaldo Guayasamín, 1999)

ALTHOUGH the universally acclaimed Ecuadorian painter Oswaldo Guayasamín reiterated in multiple interviews that he only knew how to paint, many of his comments, jealously safeguarded at the foundation which bears his name, indicate the contrary. He was humanist, a thinker, from the canvas to the word.

“The artist has no way at all to avoid his era, since it is his only opportunity. No creator is a spectator; if he is not part of the drama, he is not a creator,” Guayasamín affirmed in one of his emphatic expressions.

It was in 1982, thanks to Guayasamín’s personal retrospective of his great pictorial series, La Edad de la Ira (The Era of Rage) in museums in what were then Leningrad, Vilnius and Moscow, that I had the honor of meeting the brilliant Latin American painter.

In La Edad de la Ira, a monumental work of more than 5,000 drawings and 25 paintings, Guayasamín justifies his statement about not avoiding one’s era, since the fundamental theme of the series is war and violence, “what humans do against humans,” he himself explained.

I speak of that encounter because 14 years later, I met him again, this time in Havana, and I reminded him of that beautiful but cold Moscow autumn. With his proverbial amiability and broad smile, he called me a friend and with these words dedicated for me the notebook A Fidel en sus 70 años, edited by the Guayasamín Foundation, which bears on its cover the fourth portrait he did of the historic leader of the Cuban Revolution, whose 90th birthday is now being celebrated.

The dates of his paintings of Fidel are separated by five years, becoming a kind of talisman which cannot be left behind. This 2016 figures prominently in the pattern, marking the 55th, 35th, 30th and 20th anniversaries of the portraits Guayasamín painted of Fidel.

The first, from 1961, was unfortunately lost, and is only known from photographs, although very well documented is the story of Guayasamín’s arrival in Havana and Fidel’s posing on May 6, in a room of the already functioning Cuban Institute of Friendship with the Peoples (ICAP), on 17th Street in the city’s Vedado neighborhood.

I will, nevertheless, recount the day as recorded by Ecuadorian writer Jorge Enrique Adoum, a dear friend of Guayasamín, whose ashes along with those of the painter rest beneath the Tree of Life, a pine planted by the artist himself in the patio of his home, now a museum.

Adoum reports that these impressions were expressed by Fidel in 1999, during a workshop held in Havana, entitled “Culture and Revolution, 40 years after 1959.”

Adoum writes in El retrato perdido (The Lost Portrait) that, almost four decades later, Fidel narrated the details of that historic day and the significance it had for him, “For the first time, I subjected myself to the torturous task. I had to stand still, just as they told me. I didn’t know if it would last an hour or a century. I never saw anyone move with such velocity, mixing paints that came in aluminum tubes like toothpaste, stirring, adding liquid, observing persistently with the eyes of an eagle, making brush strokes left and right on a canvas in a lightning fast instant, returning his eyes to the astonished living object in his fervent activity, breathing heavily like an athlete on the race track.

“Finally, I observed what came out of all this. It was not me. It was what he wanted it to be, just as he saw me: a mix of Quixote with traces of famous figures from Bolivar’s wars of independence. With the knowledge of the fame already enjoyed by the painter, I did not dare say a word. Perhaps I did finally say to him that the picture was “excellent.” I was ashamed of my ignorance of the visual arts. I was in the presence of no less than a great master and an exceptional person.”

Many believe and it is an unquestionable truth that this encounter between

Guayasamín and Fidel not only produced an impressive painting, but also a deep friendship, that lasted until the painter’s death.

“One can talk about Guayasamín as an exceptional artist with great humanism, an infinitely generous man; as a dear friend,” Fidel said, speaking during the Ibero-American Summit in Havana, which recognized Guayasamín as an Ibero-American painter given the transcendence of his art, his defense of human rights and social solidarity, adding, ” as a brother ofGuayasamín, recalling him I can only express one phrase: Guayasamín was the most noble man I ever met.”

Attending the 2002 inauguration in Quito of the majestic museum La Capilla del Hombre (The Chapel of Man), Guayasamín’s great dream, Fidel described him as a “genius of the visual arts, a gladiator for human dignity, and a prophet of the future; the legacy he left to the world will endure in the consciences and hearts of present and coming generations.”

Guayasamín said that he absorbed the soul of whatever he painted – according to the Foundation’s director of International Relations, Alfredo Vera – but always said that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to absorb the soul of Fidel, since it was so multi-faceted, so he wanted to paint him several times.

And so…three more portraits. The second painted in 1981, and the fourth from 1996, are preserved at the Casa Guayasamín, founded January 18, 1992, thanks to the efforts of the noble artist and Havana City Historian Eusebio Leal. The institution was inaugurated the following year in an 18th century mansion on Obrapía Street, in the city’s central historic district, a World Heritage Site.

The third painting, done in 1986, includes the delicate treatment of Fidel’s beard with a color contrast emerging with the passage of time and is displayed at the Antonio Núñez Jiménez Nature and Humanity Foundation in Havana.

The last portrait, now reaching its 20th anniversary, is also known as “the hands of Fidel,” since the painter included them for the first time, highlighting their characteristic disproportionate shape. Once again, noticeable is the force of his work in the dramatic quality he is able to give his subjects, and how he conveys a message we all understand through the face or hands.

During his tours of many Latin American countries in the 1940s, from which emerged his first great pictorial series, named in Quechua Huacayñan (Road of tears), with more than 100 pictures, he met the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, Nobel Prize for Literature winner. During the presentation of an exhibition, the poet said of Guayasamín: “Trends pass over his head like little clouds. They never frighten him… few painters in our America (are) as powerful as this unassailable Ecudorian … he has the touch of strength; he is a host of roots; he takes on the storm, violence, imprecision. And all of that is transformed in our eyes, with vision and patience, to light…”

Guayasamín (1919- 1999) was and is, as his name indicates in Quechua, a white bird that flies. Like him, rising and enduring is his vast work, the paintings he so generously made and gave away, and the Capilla del Hombre.

(Mireya Castañeda/internet@granma.cu)