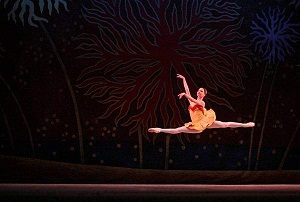

Recent seasons of the National Ballet of Cuba, with so many young dancers debuting in lead roles, coupled with a significant flow of these dancers to other countries and companies, has sparked the question as to how a ballet dancer reaches the highest category of principal dancer.

Recent seasons of the National Ballet of Cuba, with so many young dancers debuting in lead roles, coupled with a significant flow of these dancers to other countries and companies, has sparked the question as to how a ballet dancer reaches the highest category of principal dancer.

Is there a marked path to ascend to principal dancer? Do all dancers follow it? What is the impact of individual talent? Are the school, the barre, the rehearsal room, and taking on paradigmatic works all part of this path?

To decipher the steps that lead to a promotion, which are not as simple, or always as rigorous, as may be believed, and in some cases are controversial, this publication visited the office of Miguel Cabrera, historian of the National Ballet of Cuba (BNC) since the 1970s, in the Havana neighbor-hood of Vedado.

He explains that in almost every major ballet company, the ranks are principal dancer, demi-character principal dancer, soloist, demi-soloist, coryphée and corps de ballet.

There are rare occasions on which this path is not quite as linear. The BNC historian has collected first hand experiences of this, thanks to his long-standing closeness to the three creators of the company and the Cuban school of ballet itself: Alicia, Fernando and Alberto Alonso.

Cabrera was lucky enough to have Alicia herself explain, with the programs of the time in hand, that at first different categories of dancers were differentiated only by the font, the size of the letters on the program.

“You can see how in 1948, when the company was founded, the names of Alicia, Fernando and Alberto are in large letters, the only Cubans then, and those of Igor Youskevich and other U.S. figures.”

Beginning with the tour of 1949, Cabrera indicates, that they began to separate ranks and this was done according to the performance of the dancers, their technical and artistic qualities and stylistic flexibility.

The historian points out that with the triumph of the Revolution in 1959, the company was re-organized, but ranks remained unspecified. “Later in the 1960s they began to be established as the National School of Ballet was created (heir to the Alicia Alonso Academy of Ballet, which this year celebrates its 65th

anniversary). The first time was in 1962 and you will find in the programs as principal dancers Mirta Plá, Josefina Méndez and Margarita de Saa and in 1967, Loipa Araujo and Aurora Bosch.”

Emergencies forced promotions in those years.

“That’s how it was. We had no quality male dancers. Youskevich no longer came after 1959, in general due to the blockade foreigners no longer came. There was the Russian Azari Plisetski but it was known that he was not going to be permanently in Cuba and they needed to ensure partenaires (dance partners) for Alicia, for the Cuatro Joyas.”

Cabrera recalls the first graduation of the school in 1969. “From there emerged Jorge Esquivel, who Alicia and Fernando sculpted like a precious metal and by 1972 was already a principal dancer, Ofelia González, Amparo Brito and Rosario Suárez, who given other shortages rapidly performed important roles, although their promotion process was unduly delayed and only many years later did they rise to principal dancers, which was very controversial.”

Having established the school – today the national elementary and middle level ballet school with an impressive headquarters on Havana’s Prado and provincial schools in Santiago de Cuba, Camagüey, Santa Clara, Matanzas, Artemisa and Pinar del Río – the ranking system gradually took shape to become what we have today, the BNC historian explained.

“Once the youngsters enter the company, the responsibility lies with the régisseurs (stage director) and maîtres (ballet master). They follow the classes and note the progress, and according to what they see in each dancer, they prepare the cast.”

As Cabrera explains, performing center stage is not the same as being on the barre. “Sometimes they have a very good figure but not strong enough ankles, solid pointes, and many of the roles demand a strong technique. But the dancer is not all physical, he or she needs art, and it can be that someone with technique is not agile enough for certain styles, to open out, to captivate. The level of technical demand today is very high and we must add the essential element, something that can’t be obtained at school: the talent.”

Talent allows some dancers to immediately emerge from the corps de ballet, which is the essence of a great company, emphasizes Cabrera. “The corps de ballet must be uniform, all must appear equal, dance in a similar way. If the choreography has two pirouettes, a dancer does two, even if they can do five, but what happens in daily classes, is the maestro sees that a dancer can do five. And that’s the first step toward certain roles and thus, based on performance, a logical, organic development continues and as the result of cultivated talent, they can become a principal dancer.”

Is there an ideal for a classical ballet dancer? Are there any limitations due to race?

“The ideal is based on proportions, figure and the technical ability on the basis of this physique. A size is sought. It’s not that they should be taller or shorter, it is the proportion, I’m mean from the ankle to the waist, waist to shoulders, the neck. As for race, there are endless white dancers, marmoreal, who do not get to play Giselle, be it for technique, art, or physique. To dance Giselle is not for everyone, nor can everyone be a prince. I recall some princes of our company, Andrés Williams, a Black man who was a principal dancer; Carlos Acosta, a mulatto of height and proportion, a global star. I reject racial discrimination, it’s not about color, it’s about proportions, the technique and art and that they meet the requirements of the repertoire.”

To become leading figures, dancers have always been expected to dance certain pieces, correct?

“This is very much respected. For example, when men are performing Swan Lake, from the corps de ballet they pass to a pas de six, then a de trois and if they have poise and technique, Sigfrido is just behind the door.”

Is it not a ritual that ballerinas first face La Fille mal gardée, Copellia and Swan Lake before performing Giselle?

“It almost always progresses that way and today we have two young women who excel as principal dancers, Gretel Morejón and Estheysis Menéndez.”

While the established stages of development should not be violated, there is currently another emergency, if one considers that in Cuba great dancers are trained and they can now be hired by other companies. How do you view this?

“This is true, but it is not a phenomenon unique to Cuba. The modern world has a word, mobility. Here they call it political disagreement and it is not always so. In recent years, this emigration has been very strong in all fields. They go where they pay best.”

The exodus of young people who decide to try out different places, for different reasons, leaves a vacuum and logically the processes have been accelerated, the BNC historian continues, adding that the dancers reaching the higher ranks today have talent, even if this needs polishing and further artistic mastery. “Alicia has always said that when a dancer arrives from the school, they must be able to do the 32 fouetté turns from the Black Swan, Ah! That they don’t know how to place the arm properly or don’t have the perfect style is another matter.”

This is not to say that just any-one has been chosen. Already this year new dancers have debuted in important roles, who have been with the company for some time and left the school with various awards, explains Cabrera.

The historian refers to the first seasons of the BNC at the Lorca Hall of the Alicia Alonso Grand Theater of Havana, which has seen productions of La magia de la danza (including fragments from Giselle, Sleeping Beauty, Coppelia, The Nutcracker, Don Quixote and Sinfonia de Gottschalk) and the following other three works from their exten-sive repertoire: Les Sylphides, Celeste and Carmen.

These functions were a good opportunity to appreciate many of the novice dancers. Critics have noted that the young Grettel Morejón performed the second act of Giselle combining style and technique, while Adrián Masvidal, who accompanied her onstage as Albrecht, has an excellent figure but is in need of hours of rehearsal to improve his technique. The role of Myrtha, queen of the Willis, was performed by Cinthia González, who demon-strated that this other character-legend of the company is still very much alive (the late Mirta Plá is always well remembered as impeccable in this role).

Another dancer who is rapidly reaching the heights is Estheysis Menéndez. She debuted as Kitri, in Don Quixote, supported by the most recent graduate, with honors, Patricio Revé, as Basilio, who has excellent technique.

The BNC continues polishing and promoting dancers. It seems to have an inexhaustible source, but how do these rapid and sudden promotions affect the company?

“I am a concerned, trained and optimistic man. While our education system, just as it is now, continues and the maestros maintain the level of demand and curriculum requirements are met, I have no doubt, no fear about the future of ballet in Cuba. If the school is neglected then the ballet is finished.”

The organic journey from corps de ballet to principal dancer, as explained by the historian of the National Ballet of Cuba, Miguel Cabrera, exists, but there are also exceptional ballet dancers who start out with technique, physique, art, in short, a talent that catapults them to the top, and the Cuban company has had, and has, magnificent examples of this reality during its 68 years of existence. Recent names? José Manuel Carreño, Carlos Acosta, Viengsay Valdés and Anette Delgado, all jewels of the Cuban ballet school.

(Granma)